From behind the curve to full circle

27 Mar 2025

A staggering 95.5% of Australia’s resources are used for a single purpose or wasted. How to change this was a golden thread running through TRANSFORM 2025.

Australia repurposes just 4.5% of its materials – below the global average of 7.2% and less than half the European Union’s 11.5%. “How can we get more dollars out of the materials that we take out of the ground?” Professor John Thwaites AM, inaugural Chair of the Circular Economy Taskforce, challenged the packed room at TRANSFORM 2025.

Australia’s first Circular Economy Framework, launched in late 2024, outlines an ambition to double our circularity by 2035. Meeting that goal could add $26 billion to GDP annually, CSIRO modelling finds, while cutting greenhouse gas emissions by 14% and diverting 26 million tonnes of material from landfill each year.

The statistics outlined in the Circular Economy Framework make for stark reading. Per capita, Australia has the highest material footprint of the G20, at more than 31 tonnes per person. Every year, Australian firms spend $1.4 billion sending $26.5 billion worth of material to landfill. And we generate just US$1.20 of economic output for every kilogram of materials we consume, compared with the OECD average of US$2.50.

The built environment – buildings and infrastructure – presents the “biggest opportunity” for Australia to reduce our material footprint, cut emissions, save money, create jobs and strengthen local supply chains, Professor Thwaites said. For the next two days, we heard how.

Loop and learn: Lessons in circularity

The term “circular economy” suggests a complete, self-contained system – and that is, indeed, the goal. However, circularity encompasses a multiplicity of dynamic, ever-evolving strategies.

While there are plenty of practical tactics – like digital twins, material passports or reuse targets – the biggest challenge is not materials but mindset. Circularity demands new forms of adaptation, collaboration and a deeper understanding of interconnected systems. As many speakers pointed out, it requires a fundamental rethink of how we value resources.

One of the most obvious ways to improve circularity is to value and preserve what already exists. Dr Peter Tonkin, founding director of Tonkin Zulaikha Greer, presented a compelling case study of Sydney’s Green Star-rated Bondi Pavilion. The community’s insistence on a “makeover, not a takeover,” drove a sympathetic restoration of what had been an “unusable” space. By retaining 80% of the original structure, the project team didn’t just slash waste and embodied carbon. It retained the “embodied value” in what was already there, Peter said.

ISPT’s Amanda Steele shared the story of Melbourne’s 500 Bourke Street, a $160 million upgrade that saved 57,000 tonnes of carbon through reuse and recycling. Even “boring inventory” like ceiling tiles – 42,000 square metres of them – was salvaged. The retrofit also raised $260,000 for the Property Industry Foundation by repurposing unwanted furniture. Overall, the project “outperformed feasibility” – no small feat in this tough market, Amanda said.

Quay Quarter Tower, Sydney’s first “upcycled skyscraper,” stands as a prime example of circularity. By retaining 65% of its original structure and 95% of its core, the project team cut 12,000 tonnes of embodied carbon, shortened the program timeline, shaved $150 million from the budget and generated revenue a year ahead of schedule. The new components were designed for disassembly, ensuring next time Quay Quarter needs a facelift it will be easier to “upcycle and recycle the rest”, as Dan Cruddace, Partner with the architecture firm 3XN, said.

TRANSFORM’s discussions didn’t shy away from the complexity of circularity – as the case study of the Circl building in Zuidas, the Netherlands, revealed. Made primarily of wood and designed for disassembly, Circl opened in 2017 as an experimental “living lab” showcasing the potential for sustainable architecture. There was an audible collective intake of breath when Cie architect Hans Hammink told the audience it was dismantled last year after the site was sold.

This shock speaks to an underlying tension in the concept of circularity: we celebrate adaptability and reuse, yet we are still emotionally tethered to permanence. Circl was designed to be disassembled, yet its removal felt counterintuitive – almost as if it had failed. But had it? Or was this the ultimate proof of circularity in action?

From waste to wealth: Circularity at scale

“Sustainability at scale” is an enduring mantra of the Green Building Council of Australia, and circularity at scale will require more than a building-by-building approach.

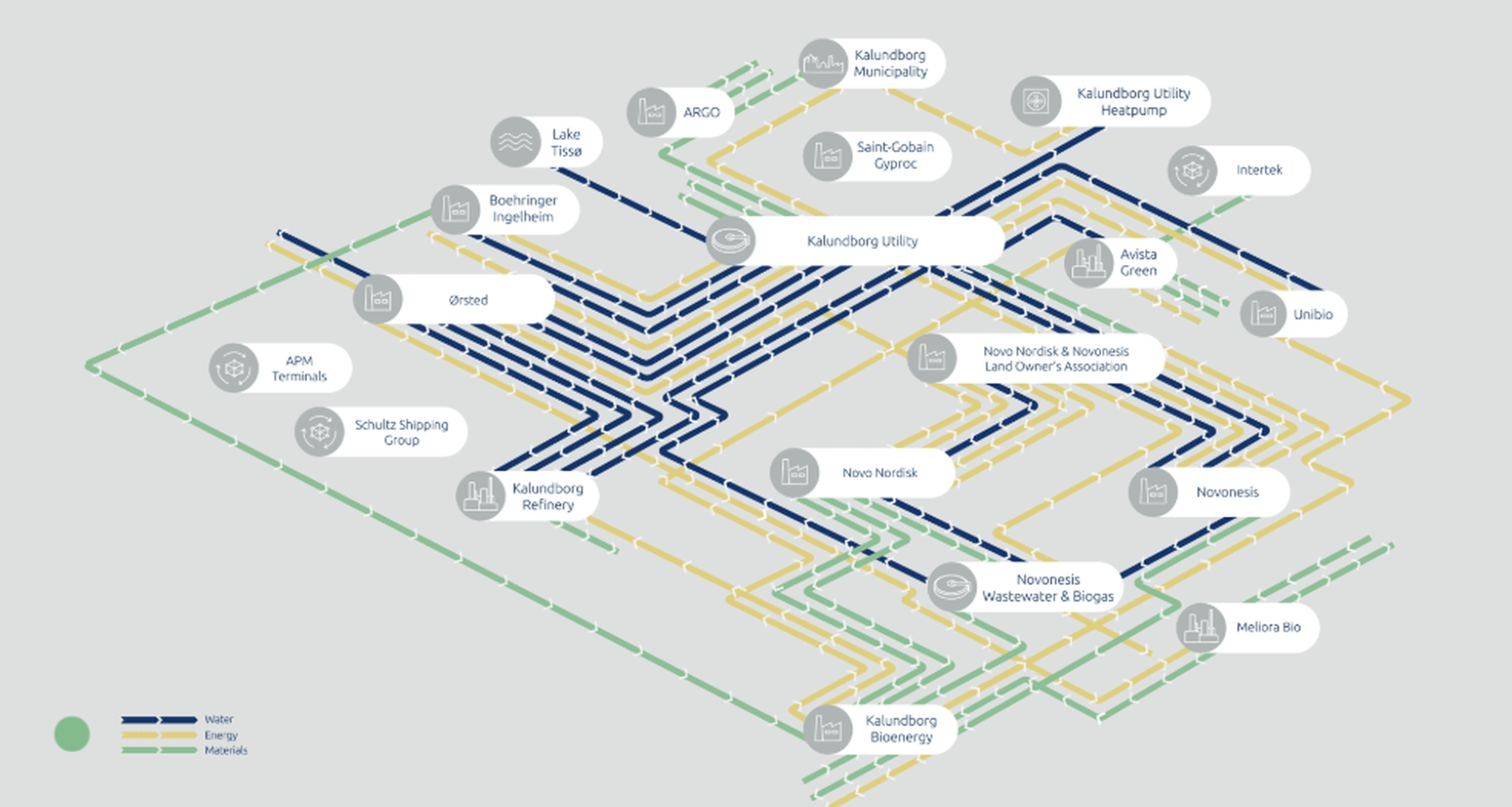

Denmark’s Kalundborg Symbiosis offers a powerful model for circular collaboration at the industrial scale. Established in 1972, today Kalundborg Symbiosis brings together 17 companies to transform residue into new resources. The results speak for themselves: 30-plus resource streams shared, from steam and biomethane to sludge and solvents. More than 586,000 tonnes of CO₂ avoided, 62,000 tonnes of residual materials recycled and 4 million cubic metres of groundwater saved.

Kalundborg also illustrates how industrial symbiosis can create economic value, providing jobs and local training, our audience heard. As Mette Wendel, Symbiosis Facilitator at Kalundborg, stated, “Systems make it possible, but people make it happen.” The first step in eliminating waste from our systems? Stop calling it waste, she said. “It’s only waste if you can’t find a use for it.”

The path to circularity begins with mindset shift, observed Andrew Taylor, CEO of the Bega Regional Circularity Co-operative. Leading an ambitious push to make Bega Australia’s most circular economy region by 2030, Andrew pointed to First Nations’ deep-rooted understanding of circularity. Indigenous Australians have practiced circular principles for more than 60,000 years, he said. We are not forging a new path but coming full circle.

From cheerleaders to champions: Building circular muscle

“We don’t see metal in a skip,” observed David Palin, Mirvac’s Head of ESG, during a panel discussion on circular procurement. The reason for this is simple: metal has clear value. It is our challenge to uncover the value in other materials, he urged.

Momentum is behind us: the national Circular Economy Framework, the Productivity Commission’s circular economy inquiry and the GBCA’s new Practical guide to circular procurement are three proof points.

The GBCA’s guide, launched at TRANSFORM, was developed in collaboration with GHD, the NSW, Queensland and South Australian governments and the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC). Its goal is to translate the lessons learnt from individual case studies to action at a larger scale. Or, as Davina Rooney, CEO of the GBCA, aptly put it: “We have enough cheerleaders for circularity. Now we need more athletes.”

The guide will help more athletes build muscle – and not a moment too soon. Day One of TRANSFORM 2025 coincided with Australia’s Overshoot Day – the day when our consumption the planet's annual biocapacity budget would be spent if everyone on Earth lived like Australians. For GHD’s circular economy specialist Huia Adkins, co-author of the Practical guide to circular procurement, Australia’s Overshoot Day is a clarion call. “We need to do more, and we need to do it quickly.”